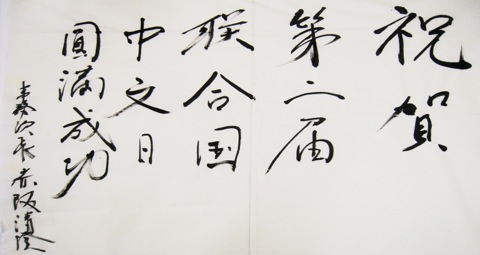

The author in China (Marketus Presswood). Reposted from The Atlantic.

People of African origin are still uncommon in China, but the infusion of international culture has started to erode traditional bigotries.

In the 1996 China edition of the Lonely Planet’s Guidebook, a text box aside comment from a street interview provided some interesting conversation fodder, “… there is no racism in China because there are no black people,” a Chinese woman was reported to have said. This became a little running joke in my small study abroad circle, since I was the only black student in my program of fifty students. It was 1997, and I was in Beijing studying Chinese. “There is no way you could be experiencing any racism in China,” one classmate sardonically told me, “because you are the only black person here.” We all laughed.

While China is officially home to 55 ethnic minority groups, the Middle Kingdom is far more ethnically homogeneous than the United States. Han Chinese make up 91.59 percent of the population, and the majority of the remaining 8.41 percent are visually indistinguishable from their Han counterparts. In part due to this difference, race and nationality are often conflated in China. A white foreigner is likely to be called laowai, or “old foreigner,” while a black foreigner is more likely to be described as heiren, or “black person.”

White Americans face no barriers to claiming their nationality, but blacks are often assumed to hail from Africa, a place thought to be more backwards and poorer than China, and one more than likely receiving Chinese government economic aid in the form of loans and infrastructure projects. This leads to either resentment or denigration on the part of some Chinese. The Chinese media tends to focus on the generosity of the Chinese government toward Africa — a sore point among Chinese who feel their government is not doing enough for the Chinese themselves — and not on the valuable natural resources gained or access to lucrative growth markets for cheap Chinese goods.

Traditional standards of beauty in China have also shaped perceptions of black foreigners in the country. In China, “whiteness” is seen as a highly desirable trait for women. Stores that sell beauty products without fail have a wide variety of whitening creams. The Chinese and Western models that fill the screen and print ads all fit one standard type of beauty — very white skin, tall, thin with jet-black hair. There is even a Chinese saying: “A girl can be ugly, as long as she has white skin.”

Growing up in the United States, I looked at Chinese and other Asian people as persons of “color” who shared a similar experience with white racism. There was some sliver of solidarity in being a “band of minorities.” For most black people or other people of color in the American cultural context there is some tacit understanding of the mutual experiences of white racism that binds seemingly disparate American ethnic groups together in solidarity. I naively took that assumption with me to China on my first visit. I did not expect that everyone would welcome me with open arms, but I did not expect what I did encounter.

My own experience in China began in the late 90s. While working for a major international language company, I taught English to Chinese people from all socio-economic backgrounds. By all accounts, my supervisors and other teachers respected my skills and knowledge in the classroom. Around 2003, however, I noticed a shift in the market and it became increasingly difficult for me to hold on to assigned classes. There were a number of complaints from students. My supervisor investigated. She clandestinely and randomly listened in on my classes via the company intercom system. After a couple of weeks she called me into her office. She told me I was an excellent teacher and could find little fault in my methods and teaching of the prescribed curriculum. Students just wanted a “different” teacher.

While on break, I overheard students speaking in Chinese about how they were paying so much money and wanted a white instructor. One student went so far as to say, “I don’t want to look at his black face all night.” There was nothing my supervisor could do. The market was demanding white teachers and the company was responding to that demand. Not only did they want white teachers, they wanted attractive ones. I overheard a number of students discussing and comparing the physical attractiveness of one teacher over another. Students were even willing to accept a white, non-native English speaker over a black, native English speaker. This was a far cry from my first days of teaching English in China in 1999, when students were just happy to have an English speaker in the room.

In the first half of the 20th century, Chinese and black American intellectuals frequently collaborated. Langston Hughes, the world-renowned black American writer and poet, met Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature, in Shanghai in the 1930s to work on theories and language for a universal, pluralistic, transnational form of cooperative nationalism. Paul Robeson, a professional actor/singer and social activist, was also a staunch ally of China’s. He actively fundraised for the Chinese Defense League, the precursor of the China Welfare Institute founded by Soong Ching-ling, the wife of Sun Yat-sen, a Chinese revolutionary considered to be the founder of the Republic of China (ROC). He also popularized the current Chinese National Anthem, the March of Volunteers, to a global audience by singing the song in Mandarin Chinese for audiences around the world. A number of other black scholars visited China during the first half of the 20th century, including W.E.B. Dubois, one of the founders of the NAACP, and Rayford Logan, a Howard University history professor.

While in exile in Cuba in the early 60s, black internationalist Robert F. Williams corresponded with Mao Zedong to support the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. Mao wrote his, Statement Supporting the Afro-American in Their Just Struggle Against Racial Discrimination by U.S. Imperialism on August 8, 1963. He declared:

I call on the workers, peasants, revolutionary intellectuals … whether white, black, yellow, or brown, to unite to oppose the racial discrimination practiced by U.S. imperialism and support the black people in their struggle against racial discrimination.

Mao issued another statement of support in April 1968 after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. But despite these expressions of support, there is scant evidence to prove Mao or any other Chinese political leader at the time would have been willing to align themselves actively with the Civil Rights Movement. In fact, Chinese foreign policy in the 1960s mirrored much of that of the West, due in part to the Sino-Soviet split and the coming détente with the U.S.

After the deaths of Mao and Zhou Enlai, the era of alignment with the developing world and oppressed peoples gave way to Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatic plan for economic development epitomized by his statement, “To get rich is glorious.” From the 80s to the present, this new mantra has fueled a single-minded devotion to the pursuit of wealth, leaving little room for concern with past ideals. The isolation of China in the decades before its economic coming of age also limited the exposure most Chinese had to people of other ethnic origins, creating a vacuum of knowledge, drawing in stereotypes and prejudice.

Unlike their parents and grandparents, China’s youth have grown up with access to information, entertainment, and art from all over the world. Many have consequently come to reconsider stereotypes of black people, and they are in turn influencing the opinions of their older, more “traditional” relatives. The popularity of American popular culture in China, particularly the NBA, which as of 2011 was made up of 78 percent black players, is an example of this. The NBA has over 41 million combined followers on Sina and Tencent micro-blogs, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter. The Chinese Basketball Association estimates that there are 300 million people in China who play basketball. NBA stars flock to China on multi-city tours every summer to greet crowds of adoring fans.

My Chinese wife recounted a story of her younger cousin, who became a huge Allen Iverson fan to the dismay of her mother. During every game, she would don a Philadelphia 76ers jersey and plop down in front of the TV to cheer on her favorite basketball player. In order to spend more quality time with her daughter and understand her better, the girl’s mother began watching games with her child, and in no time became an avid Sixers fan as well.

Another friend related a story of about his uncle in Beijing, who sent his high school daughter to America for a summer camp. At the end of the camp, during the parent pick-up, his daughter burst into tears as she said goodbye to her summer camp roommate, who just happened to be black. The Chinese father recalled thinking, as he surveyed the scene of his emotionally distraught daughter, “I never thought my daughter could have such an emotional connection with a black person. Maybe I need to rethink my biases.”

Many black people from around the globe are living, working and traveling in China now. Some of us are American, European, Latin American and African, with a wide range of cultures, languages, religions and professions that defy neat categorization. While different histories have been a source of racist ideas and assumptions, perhaps our shared present and future will give Chinese a reason to reflect and reconsider.

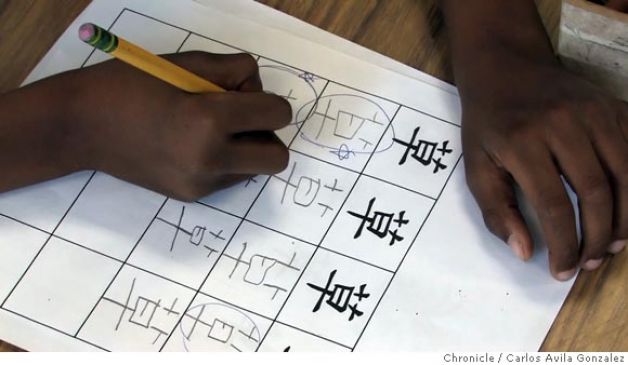

Parents enroll their children in language immersion programs in order to give them the gift of knowing another language. They also expect that their children will do as well or better in learning the regular curriculum in the immersion language as will children who are learning that content in English. As a result, there are two fundamental strands of student assessment in elementary immersion programs: assessment of student learning in various subjects taught in the language, (e.g., math and reading); and assessment of the student’s proficiency in the immersion language. Both are used to evaluate individual student progress, to report to parents and the general community, and to support continual program improvement.

Parents enroll their children in language immersion programs in order to give them the gift of knowing another language. They also expect that their children will do as well or better in learning the regular curriculum in the immersion language as will children who are learning that content in English. As a result, there are two fundamental strands of student assessment in elementary immersion programs: assessment of student learning in various subjects taught in the language, (e.g., math and reading); and assessment of the student’s proficiency in the immersion language. Both are used to evaluate individual student progress, to report to parents and the general community, and to support continual program improvement.