Afro-Kawaii: From Early Cultural Exposure to Lifelong Passion

Many of us wonder how immersion education and exposure to Chinese culture will influence our children’s future. Here is one woman’s experience to help us see the possibilities.

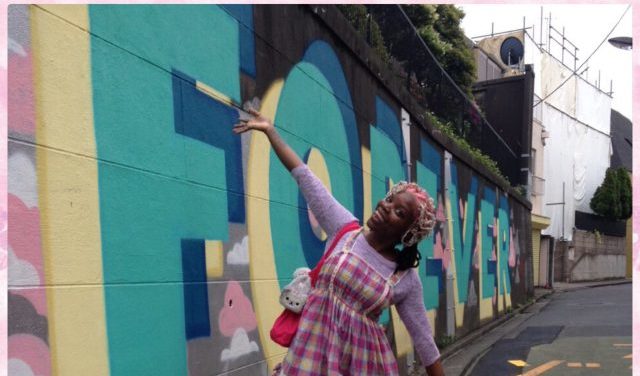

In elementary school, Imani K. Brown participated in a short-lived Japanese cultural exchange program that changed the course of her life. While growing up in one of Washington, DC’s predominantly black neighborhoods, her fascination with Japanese culture and creative arts secretly continued to grow. Now at age 38, Imani has blended her own creative talents with her passion for kawaii (cuteness) culture to build a profitable business as a tattoo artist and illustrator and a unique aesthetic that she calls Afro-Kawaii.

Her company, I.P. Brand Ink & Art Creative House, includes Little INKPLAY Shop, “an empowering creative atelier and kawaii culture hub” located just outside Washington, DC and IP Brand VC + BI, a branding and coaching service for creatives. As an illustrator, she is creating a line of manga characters featuring Ippie-chan and her fabulous Afro.

Imani is also heavily involved in DCKawaiiStyle, a soon-to-be-nonprofit created “to introduce & promote the philosophy of kawaii (cute) culture as a fun, happy & positive lifestyle alternative to residents in the DMV area and abroad.” One of the organization’s projects, Kawaii in da ‘Hood, engages black and brown youth in Japanese-related hobbies and introduces them to their practical application as professional ventures.

For the past six or seven years, Imani has taken “working vacations” to Japan, documenting her travels at dctojapan.com. She studied the Japanese language long before her first voyage and has become more fluent over the years.

Although Imani’s focus is on Japanese rather than Chinese culture and came out of traditional school rather than an immersion setting, PAASSC brings you this interview to provide another view of how African-American students experience early exposure to other cultures and how it may impact their future goals.

What attracted you to Japanese culture, and kawaii in particular? How did you get interested in kawaii culture?

Imani: I was in one of those TAG (Talented and Gifted) programs that was a Japanese culture exchange. We were doing cool stuff: learning to eat with chopsticks using M&Ms, writing kanji, just learning to see the world in another culture’s eyes. They took it away, no explanation, but from that moment on, I guess the interest just stuck.

I was learning other cultures, things that we’re not in tune with in America. I was like, “Oh wait, parents actually encourage their kids to do anime and they do it together? That’s cool!” Certain things that you don’t see in everyday American culture, I started thinking of as a kid, like “I wanna do that, I want to be able to experience that. This is what I want for my life.”

It took some time before you felt comfortable to openly engage in it though?

Imani: Growing up in the hood, you couldn’t be a nerd outwardly. You’d get beat up. I had to fight to do my homework. My mom’s rules were that before you go to play, you have to do all your homework. People in the neighborhood would think I was trying to be better than them because while all my friends were playing, I was sitting on the porch watching all of them and doing my homework.

So the idea of being a nerd, otaku (a Japanese term that loosely translates as a fan, often applied to anime and manga fans), kawaii lover, anything like that just wasn’t something that I’d do outwardly. Anything that brought more attention, I wasn’t with it because then you’d just be fighting for your existence. Being black we’re already fighting for our existence. So there’s not much I want to add on to that.

But it was so much a part of my hobbies, and your hobbies become a part of you. It was a part of me that I wanted to be able to come out when it wanted to.

How did you end up visiting Japan so much?

Imani: My first time was only one week. In 2010, I wanted a vacation. I felt like I deserved it, and I paid for it with my own money. I had sent out these formal letters of artists I wanted to meet. I didn’t just want to show up at their studios. I had my then-Japanese teacher help me write the letter. I emailed it to 3 of 4 artists.

My now-senpai (mentor, teacher) and good friend Naoki of TNS Tattoos was the first and only one to email me back. He was like “Come, I want to meet you.” I went to Osaka for the weekend, and I got to do a tattoo and plan my next trip to Japan [for the King of Tattoo convention in Tokyo]. The rest was history. He trained me into considering that I would come back every six months.

Most other countries and cultures get two weeks to a month of self-care time for an entire year. I figure I deserve my two weeks to a month. If anything, I make sure it’s a working vacation in Japan – that way I can appease feeling like I’m not working or pulling my weight, but at the same time I can take a break from what we know as America, or being black in America, do some self-care, do some self-exploration, have a peace of mind for a moment, and then come back to the rat race.

What was it like to travel in a foreign culture that you had such a deep interest in?

Imani: I think I felt like an outsider because of my own mind, my own learning curve, my own nervousness, fear of the unknown. But I was accepted as if I was one of the crew. Not necessarily as far as being Japanese but like, “This girl is legit. She likes the same things. We can connect over hobbies and then have deeper meaning, dig deeper from there.”

That’s something you don’t necessarily get a lot over here. I made lifelong friends on the internet before I even met them in person. We’re doing language exchange for like five years before I ever made it to Japan.

People were genuinely helpful and they’re not asking you to return the favor in any way. Over here, we’re bred to think if someone does something nice for you, you automatically owe them. Over there it was like, “No, Imani, put your money away, we’re going to go do this. What do you want to do today? I’m going to take off work today to spend time with you.” It sent me into panic like, “Oh, now I owe you, I’m going to have to give you all my money, I was not prepared for this.”

What is it like to be black in Japan?

Imani: I don’t have to leave the house and defend my blackness, my very existence. I don’t have to worry about somebody saying some racist remark.

Don’t get it twisted – it’s not that those things don’t happen, microaggressions don’t happen. There are tons of black people in Japan, so I definitely have heard stories, I’ve definitely seen things, they just haven’t been done to me.

I’ve only had one racist experience in Japan from Japanese people directly, and that was when I first started going over there. My friend was like, “They’re bullying you because they think you’re there as a novice and you don’t know how to speak, you’re not in tune with the culture. So they just pick on you. So we just gotta get you speaking so you can talk to people and that will shut that door.” It’s never happened again. Anything else racist has been a few incidents in my friends shop by French people.

I’m sure if I stayed longer, I’d experience more than what I actually have experienced, but if you had to compare apples to oranges, I’ll take the oranges right now.

How do you define Afro-Kawaii?

Imani: Kawaii means cute in Japanese. There’s a specific aesthetic that goes with Japanese style, but at the same time, I can take something like that and rock my locs as opposed to trying to rock a shorty wig. I wanna be able to wear Lolita (the ultrafeminine doll baby style of dressing associated with kawaii culture) and sit down in a drummer’s circle and hit a djembe drum. That is Afro-Kawaii to me.

Once a year, I do a Kawaii Kwanzaa Challenge in cute aesthetic, looking at the principles everyday, making intentions for myself. There’s a thing called kawaii journaling so I did that with my Kwanzaa Challenge and put both lifestyles together: what my blackness is to me and my name, cause my name is all Kwanzaa, and what I’ve been able to appreciate, garner, and what’s helped make me a better person from kawaii all at the same time.

Is there anything else you want to share with the PAASSC families?

Imani: If I may, please make sure your kids are grounded in their own blackness, in their own culture. I’ve seen black kids, black girls end up in kawaii culture, and they love it. But they wanna mimic what Japanese are doing, not find their own way to appreciate what Japanese are doing and wrap it in their blackness and make it their own.

Kids will be able to find themselves even more by experiencing a whole other culture, but it would take them being secure in their own blackness first. So even if they decide they want to travel to China, they’re not losing themselves in Chinese culture. They’re gaining appreciation and value from Chinese culture, and they can take certain things and add it to their own lifestyle and culture to create their ideal lifestyle.