By Jamila Nightingale

My family’s road to Chinese immersion began just days after my husband and I walked down the aisle. While we were honeymooning overseas we came across a short article on raising bilingual children. The article posed a question: Which language would you choose, Spanish or Chinese? This sparked a five-minute conversation during which we briefly discussed the benefits of raising bilingual children, quickly agreed that we saw the benefits and decided on Chinese, specifically Mandarin.

Nine years later, both of our young daughters are enrolled in a full-time Chinese immersion school and I have started a parents’ association to support other African American families who have selected this route for their children. Following this nontraditional path hasn’t always been smooth, but like the Ashford and Simpson song that played when we took our first steps from the altar, “We built it up and built it up and now it’s solid–solid as a rock!” We are happily committed to Chinese immersion education.

In this essay I’ll elaborate on our experiences with Chinese immersion and connect it with those of several other African American families I have met through Parents of African American Students Studying Chinese (PAASSC). I hope I can give a sense of what motivates African Americans to pursue Chinese immersion education and how some of us have experienced it. I emphasize “some of us” due to both the small sample size–nine families–and the specific demographic that we represent: married, middle-class, San Francisco Bay area couples (several are interracial), all college educated (several have earned advanced degrees) and internationally traveled. Many of the parents mentioned in this article are themselves fluent in at least one language other than English; some speak two or three. As Chinese immersion takes off in communities throughout America, African American families from diverse geographic, economic, educational backgrounds and family structures will likely echo some of our experiences while adding other perspectives.

Why Immersion?

At the heart of the interest in language immersion is, of course, a family’s desire to raise a bilingual child. This desire is often rooted in the parents’ high aspirations for their child’s education and in their own values and exposure to other languages and cultures. As I mentioned above, our interest in bilingual education began with international travel and a magazine article. We agreed that our job as parents is to give our children better opportunities. In considering the opportunities we had as children one that didn’t come until later was learning another language.

Other parents were drawn to the many benefits that being bilingual offers their children. “Being a teacher, I know that language learning enhances cognition,” says Dawn Williams Ferreira. “We wholeheartedly support language learning and have always thought that our children would be multilingual.” Giving her son a global perspective attracted Tracey Helen to multilingual education. “We live in a big world,” she says. “The more languages you speak, the more you can learn and the more people you can have relationships with. I think Americans isolate themselves; the rest of the world, they speak multiple languages.” For Andie Acuna, language immersion was a way to help her son “understand how differences in culture are a strength instead of a barrier to understanding/appreciating.”

Once we decide to give our children the gift of a second language the next decision is which format works best for them. Whether the parents speak one or multiple languages themselves, they have to weigh the pros and cons of language immersion vs. traditional language education for their child. Heneliaka Jones chose immersion over a typical foreign language class because she wanted her daughter to understand another country’s culture as well as its language. “We want her to know how to tell and receive jokes in the language,” she notes. “That’s when you know that you understand the culture–when you understand the nuances/idiosyncrasies of the culture.” Jones’ emphasis on the cultural aspect of language learning is based in her own international travel, which began when she was still a student: “As much as I appreciated the cultures, the barrier was the language,” she says.

Like Jones, most African American parents weren’t raised by bilingual parents or in a bilingual home. So while articles and experts may inform us that dual language immersion programs are a great educational opportunity, those of us without direct experience of being bilingual are walking by faith. We can’t truly understand how those benefits will manifest until we see it happening in our own child. For example, I had to explain to my grandfather that my daughter might actually dream in Chinese to help him understand what this process may mean for her.

I wish I had had the benefit of Lia Barrow’s advice back then. She encourages parents to examine their own motivations for language immersion. “If you want it so that your child can access better jobs and for that reason alone, you will be undoubtedly be in for more work than you expect,” she cautions. That’s exactly what I discovered.

In my family’s case, we put our eldest daughter in a Saturday Chinese language class when she was three years old. By the end of the 12 week course, I had decided that the lure of raising a bilingual child was more time-intensive than we could manage, especially since she had only learned about three words and there was no way to support her language learning at home. Because of that, my husband and I decided to discontinue our pursuit to raise a bilingual child until a fortunate set of coincidences–not the least of which was our daughter’s insistence on returning to Chinese–drew us back.

Why Chinese?

In surveying PAASSC-affiliated parents, I learned that while bilingual education was a high priority for each couple, my husband and I were one of the few that specifically sought out Chinese as the language of choice. For instance, Helen actually started her daughter off in a French-language daycare before enrolling her in Chinese pre-school, and plans to reintroduce French at a later date.

Several factors influenced our family’s preference. Our early research indicated that once a child has a second language, additional languages are easier to pick up. Spanish is Latin-based and therefore easier to learn. Also, my husband understands and speaks enough Spanish to hold a conversation, or at least to understand one. By contrast, its unique script and syntax make Chinese the most inaccessible language to us, so it seemed to make sense to start with the most difficult language. And when you look at the globalization of the world, there are a billion Chinese who our daughters would be able to talk with.

The Barrows didn’t specifically decide to enroll in Chinese immersion. “We decided that our son needed more of a challenge in school. We were open to Spanish, French, Japanese, anything.” Jones also sought general bilingual education first and foremost. She says that “over time we began to see the benefits and necessity of learning Chinese.” In each case, it was the atmosphere and promise of the specific school, rather than the language itself, that appealed to these families.

As Barrow’s earlier advice implies, earning potential is another motivator for parents who select Chinese over other languages, even if it does require more work. “We looked at what we could do to prepare him for the future,” says Acuna, “and decided that based on the economic movement of the country, a brown boy with Mandarin language skills would be able to write his own ticket in various industries and be able to work anywhere in the world.” The age of the language and its character-based script attracted Ferreira. “The characters communicate language in a way similar to Egyptian hieroglyphics so thinking in terms of characters versus phonetics is also interesting,” she notes.

Some parents were not looking for immersion at all, but found it by happenstance. Tony Hines, a mother of four and fierce community advocate, was recruited to enroll in the Mandarin immersion option by the principal at her daughter’s school, Starr King Elementary School. Bernadette Jackson was attempting to enroll her daughter in the same school that her older children attended, but the general education program was full. She chose the Chinese immersion education option so that children could go to the same school.

However they come to it, most African American parents who pursue a Mandarin immersion education for their children come to realize that Chinese immersion programs provide their child with a strong math and science curriculum, teachers that have high expectations for their students regardless of ethnicity, and challenging, stimulating curricula and lesson plans.

Overcoming Resistance

When we first reached out to friends and parents for their advice, many were curious about our interest in a Chinese immersion program, but very few supported the idea. In fact, there were only two friends in our corner. Luckily, these two parents were the ones whose opinions we most valued. I also found an ally in our daughters’ godmother, who had enrolled her own children in an independent school. After I shared the doubt and dismissiveness of our family and friends with her, she encouraged me by saying, “If I had a chance to do it again I would choose a language immersion school for my children. You are a trailblazer and should not let this opportunity pass you by.”

Regardless of the source of resistance, the issues raised fall into two categories; academic and cultural. In the first category, our friends questioned how our children would learn to read and write English in an immersion classroom. How I would correct their homework? How would I support their Chinese language learning? These are valid concerns facing every monolingual parent of a bilingual learner. Helen addresses the reality of language acquisition in 100 percent immersion settings, especially at an early age: “My daughter’s program is all Mandarin until she gets to a certain grade, so it’s not surprising that English skills will be delayed. It catches up by the second or third grade.”

African American families are faced with additional hurdles based in historical and current stereotypes that some Blacks and Chinese hold about one another. These range from how Blacks are portrayed in the entertainment and news media to perceptions that Chinese (and Asian Americans in general) own all the stores in predominately Black neighborhoods and mistreat Black customers. “My mother was very concerned with how ‘they’ were going to treat her granddaughter,” says Jones. “We told family and friends, ‘You have to trust our judgment.’”

I had reservations as well, mostly about whether Chinese teachers would be able to provide a culturally supportive learning environment for my children. Both my husband and I had attended primarily white schools growing up. Unlike him, however, I had a lot of resentment about it, and I didn’t want my daughters to be isolated in their schooling or disconnected from a rich African American cultural experience. In today’s predominately white schools, especially in the Bay Area, diverse cultural heritages and traditions are celebrated. Chinese immersion schools, by their very definition, focus on Chinese heritage and culture.

As a social worker, I recognized the value of providing my daughters with a progressive education, which a number of Bay Area schools offer. Such schools are built around a curriculum that teaches students the benefits of using non-oppressive language and engaging with diverse communities in a manner that honors and respects their community structures. It is important for me that my children understand that there are diverse family structures and diverse family values. This is often conveyed in the classroom and through service learning projects.

I am a strong supporter of the learning opportunities that come through community service, but I find that too often, such projects are unidirectional; that is, they involve affluent students donating resources to underserved schools or communities. A non-Mandarin immersion school that ranked high on our list developed an innovative project that involved eighth graders in mentoring and tutoring students at a local underserved school, and fifth graders from that school providing reading and mentoring to the first school’s primary students. This creates a reciprocity of service that helps students to see that an “underserved” community has valuable gifts and talents to share as well as needs that must be met.

I felt discouraged by the lack of these progressive education elements in the local Mandarin immersion schools we were considering. However, I had the benefit of a husband without my concerns, fears and need to advocate for diversity. He consistently emphasized the benefits of the language immersion experience. When I wanted to back out he stayed firm and pointed out that it would be our job as parents to compensate in those areas where the school lacked culturally and progressively.

So far, my daughters don’t show any signs of feeling culturally isolated in their immersion programs but they are still very young. Forming PAASSC was in part, a way to prevent feelings of isolation. It allows them to regularly interact with up to a dozen other African American children who speak Chinese. PAASSC also gives us a vehicle to develop relationships with students from different cultural and socio-economic communities and create opportunities for reciprocal service learning outside of the classroom.

“Do” Diligence: Finding the Right Immersion Program

While the presence of a few immersion-friendly allies helped overcome my resistance, Acuna recommends “acknowledging your fears and facing them head on by asking questions.” She offers interested parents four ways to soothe concerns with actual information:

1) Go to the school and spend time on campus to observe how the staff engages the students, peer-to-peer relationships, etc.;

2) Talk to administrators, teachers and other parents to assess whether the school will be a good match for your child and your family;

3) Be patient;

4) Actively participate.

It’s also a good idea to identify what’s most important to you and find a school that most closely fits your goals and values, whether you opt for a public, private or parochial school. These proactive measures are a recurring theme in each of our families’ stories of how they fell in love with their particular school. My family’s case involved a good bit of trial and error, and serendipity as well.

Every new parent has many hopes, dreams and expectations for their first child. Education was one of my primary interests when my oldest daughter was born but I was shocked to learn that I was behind the curve when it came time to put her in day care. The best centers had waiting lists of parents who had signed up shortly after conception, while I had waited until my daughter was four months old – two months before I had to go back to work. After struggling to find day care, I was determined not to let a lack of awareness cause us to miss opportunities for a top-quality kindergarten. The search for kindergarten just happened to correlate with my daughter’s requests to return to “Chinese school.”

You see, after that 12-week introduction to Chinese in the Saturday program, my daughter was captivated. At the wise age of three she repeatedly informed me that she didn’t want to go to dance class on Saturday and wanted to return to Chinese class instead. While we were weighing the decision to pursue a Chinese immersion experience, Alameda County was in the process of confirming Yu Ming Charter School as the first Chinese immersion charter school in Oakland, Calif. (The only other public Chinese immersion school in the East Bay is in the Hayward Unified School District.)

At the time, I was teaching at California State University–Hayward, so I used the university’s research resources to educate myself on language and cultural immersion. I was dismayed to find that there wasn’t much literature on the benefits of bilingual education for African American youth. What little there was came primarily from doctoral students, covered a variety of immersion programs in the United States, Canada and Latin America and focused on several languages, including French, Spanish, German and even English.

As I mentioned earlier, diversity was important to me, and my direct experiences with African American parents pursuing Chinese immersion schools for their children confirmed what the girls’ godmother said: that we were on the cusp of a new trend that should not be denied to our children. In working with Yu Ming to confirm their charter, I was impressed with the number of other African American families that had stepped into leadership positions to ensure that Yu Ming’s charter was approved.

Dawn Williams Ferreira and her husband were among them. They weren’t new to language immersion–their oldest child was already enrolled in a Spanish immersion school and Chinese lessons. So when they heard that Yu Ming was opening in their neighborhood, they enrolled their middle son and became part of the first group of parents to get the school off the ground. “Being a founding family meant that we were very involved in making sure that other Black children attended the school,” she says. “We did not want our child to feel isolated and we understood that we had a responsibility to make it the school that we wanted for our child.”

The presence or lack of diversity helped Helen decide between schools that weren’t very different in their academic structure. “I realize that’s a conscious choice to have diversity or not. And from my perspective, that didn’t seem important to them,” she says of one school that she crossed off the list.

Barrow and her husband were committed to the public school system and preferred one close to home. So while language immersion had been a latent interest for them they didn’t actively pursue it until they were accepted in the lottery at the first full-time immersion school in their district, where Chinese happened to be the target language. Acuna’s priorities included “identifying a school where the teachers were kind and loving to students” because it matches her belief that “kids who feel supported in learning learn better.” Barrow and Acuna are both the parents of children with special physiological and learning needs so it was extra important that they felt comfortable with the school’s capacity and willingness to be both responsive and sensitive, especially given the language difference.

The cultural aspect of immersion, teaching style and parent community helped Jones’ family fall in love with their daughter’s school: “When you walk into the school, it’s like walking into China. The landscape of the school, the classroom design, the learning tools, etc. It’s also a Montessori curriculum in the Pre-K, and our daughter is a hands-on learner.” She cautions against basing your total impression of the school on open houses and similar recruitment activities: “Admission tours can be scripted. We attended events prior to enrollment.” Those activities helped her family get a ‘backstage’ view of the parents, teachers and students, so to speak. “When we went to events outside of Admission events, we were well embraced by the community and felt connected,” she notes. “If we didn’t feel comfortable we would not send our child.”

Where the Rubber Meets the 道路*

However thorough one’s research process may be, the real “fitness” of immersion education – and a particular school or program–can only be gauged once your child is enrolled. We were amazed to witness that our oldest daughter’s natural talent for language and learning exceeded our expectations. A few parents have told us that she is “the best Chinese speaker in the classroom.”

Unfortunately, her report card did not reflect that level of proficiency at first. Her teacher initially stated that my daughter wasn’t interested in reading Chinese books, even though her English class marks were higher than those for math and social skills. Because she had been so persistently enthusiastic about Chinese we signed her up for a more intensive Chinese language class. She actually looked forward to the extra work. When I asked her about the class she stated that she really enjoyed it because “the homework is more challenging than her homework at school.”

Our youngest daughter’s affinity for Mandarin has been even more surprising. She looks to her older sister for guidance but displays much more confidence, grasps the language more naturally and earns higher marks on her report card. We believe this is the result of her exposure to Chinese for almost as long as she has had been speaking English; thus, when we enrolled her in the program she already knew many of the songs and was able to initiate fluent sentences.

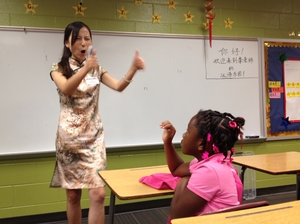

All of the parents we interviewed found similar success in both their children’s classroom performance and enjoyment of the experience. Ferreira says that her six-year-old son’s teacher “joked that he speaks so well that he is beginning to argue with her in Chinese.” Helen’s daughter is doing well in her second year of pre-school. “She can’t really read the books but she’ll pretend read it,” she says. “She likes to speak Chinese at home, she likes to sing in Chinese. Sometimes she’ll try to teach momma Chinese.” Jones is thrilled to watch her normally shy three year old become more enthusiastic and participatory in classroom activities, though she admits that this blossoming could be due to normal development or the school’s teaching style, or perhaps both.

Likewise, Acuna has watched her six-year-old son improve in both Mandarin fluency and self-confidence in the three years that he has been enrolled. “Initially his proficiency in understanding was growing but not his willingness to speak it. Now he is so confident and gets great feedback from his teacher and while we are out in the community.” She credits the teacher’s style with this improvement along with the school’s willingness to support her son’s Individualized Education Plan (ADHD, Inattentive –one of three subtypes of ADHD, which specifies the low attention span vs. hyperactive-impulsive behavior) and his specific needs. She explains how his teacher worked within his limits by agreeing that he would only be required to speak in Mandarin until lunchtime. “The teacher has stated that he continues past lunch, although the other children don’t speak primarily in Mandarin,” she says. “The experience has been an excellent challenge for him.”

It almost goes without saying that whether traditional or immersion, not all schools or teachers are created equal. Add each child’s unique needs and personalities to the mix and challenges will inevitably arise. Teachers spend so much time influencing our children that a problematic relationship between them can be a deal breaker for the entire immersion experiment. It is easier to walk away than to remain committed, particularly with so many other educational options available.

In one instance, an African American mother consulted the classroom teacher, the teacher’s aide, and even another parent about a problem her child was having, but she was unsatisfied with their responses. She was ready to give up but gave it one last try and approached the principal who was so responsive that she was encouraged to persevere. The lesson here is that it may take multiple attempts to find an administrator or teacher who “gets it” and it may not be the person who is directly responsible for your child.

Barrow faced a situation that highlights the specific cross-cultural differences and expectations that can arise in an immersion setting. She has raised an eyebrow more than once at the dominant instructional style of her son’s teachers, all of whom are native Mandarin speakers from mainland China or Taiwan. “California is advanced in looking at what classroom environments are good and healthy for encouraging student growth,” she notes, “but most of his teachers have very little fluency in English and very little understanding of the American cultures/customs. They seem used to students being docile and obedient and are open to calling students ‘bad’ if they don’t seem to conform. On my son’s report card, the teacher actually wrote that he ‘is very often bad in class.’”

Helen had a similar experience during her daughter’s first year in Chinese immersion. Recognizing that the school’s administration did not have an effective structure for communicating with the parents, she says “the onus was on me to really get out there in the second year to do the work and make the relationship.”

These families’ approach to resolving their issues demonstrates how active parental involvement can create a solution-oriented climate. Neither of them removed their child from the school; in the Barrows’ case, they met with the teacher to explain why “bad” was insufficient to explain what their son was doing, to obtain clearer descriptions of the undesired behavior and to express their disappointment at the school’s lack of response to their requests for feedback prior to the report card distribution, especially given his medical history. “We have to provide the staff with space for a learning curve,” Barrow explains.

She’s been pleased they did. Despite their concerns, her son is flourishing in both his language facility and in his mastery of other subjects. “He was recently diagnosed with epilepsy and it has become increasingly difficult for him to read and write in English, but it doesn’t seem to affect his Mandarin. So development of his math skills have not been impacted (math is taught in Mandarin), and the continued development of his Mandarin language seems to have helped his English reading and writing.” The fact that he’s thriving is the most crucial part for her. Even if he were in a school that was more culturally competent, if her son wasn’t thriving she wouldn’t keep him there, she says.

And speaking of cultural competency…

Black History Month or Chinese New Year?

I’ve said that one of my reservations involved an immersion school’s ability to provide my daughters with a rich understanding of their own African American heritage. As much as Chinese immersion programs promote their focus on the whole child, it’s also clear that they offer a heritage-based education that is often devoid of the African American experience. Several of my fellow parents shared my husband’s view that we would have to assume primary responsibility for this at home.

The Ferreiras accomplished this by enrolling their son in an Afrocentric homeschool before he began attending Yu Ming. “Parents should reinforce home culture first,” says Dawn, who credits that experience with strengthening his sense of self, confidence and pride in his own heritage. “Children need to really love themselves before they can appreciate other cultures.”.

I also came to realize that “cultural competency” means different things to different people, even within my own race. Barrow applies this term to explain the school’s understanding of California’s educational expectations as well as broad American social customs. Jones, on the other hand, uses the phrase to describe the school’s ability to impart the subtle rules of Chinese culture. “Black History Month would be nice,” she says, “but for families who want a child to learn Chinese that’s not a deal breaker. We read the mission statement right away. They were very clear on what their focus is.” She went on to state that as her daughter’s first role model, it was her job as a mother to instill a sense of self-esteem and cultural pride. At the same time, she monitors her daughter for “any signs of disrespect or feeling inferior, use of pejorative terms on the playground, feelings of a child being targeted because of color or differences.”

Barrow echoes Jones’ emphasis on the family’s role in balancing Chinese culture with African American heritage: “I don’t expect the school to reach the level of what I am able to provide for my son as it relates to his cultural identity and history.” Because the staff at her son’s school is so new to America and our culture, she finds that they are learning about this nation’s history–including the history of African Americans, Latinos, women and gay and lesbian people–along with the students. Ferreira adds that “the responsibility is on us as parents of children of African descent to make our presence known. We, as parents, have come together for Kwanzaa celebrations at the school and Black History Month presentations. We organize this on behalf of our children.”

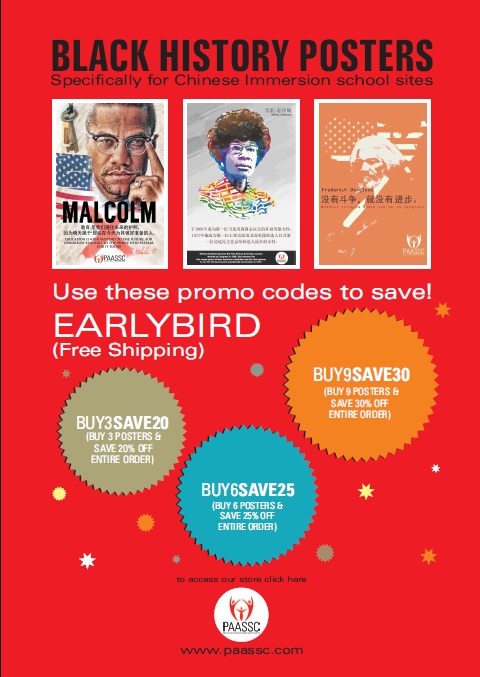

For my part, I did not want my children to feel like they were “the only” Black students learning Chinese. This was a big factor in my decision to start Parents of African American Students Studying Chinese (PAASSC). Our earliest events were simple play dates where children could come together and practice their Mandarin skills. As our network of parents continues to grow, we will expand our efforts to educate families that may be interested in Mandarin immersion, assist administrators and teachers in building their capacity to deliver culturally competent and anti-oppressive education, and connect our mostly monolingual parents with resources that empower them to support their children’s academic development even though they don’t speak the target language.

The need is especially great in the third area: Of the parents I interviewed, only three were actively supplementing their children’s Mandarin education with extra-curricular activities. Many do not have access to age-appropriate Mandarin resources beyond a few tapes and movies they find in Chinatown. I had the great fortune of traveling to Beijing at the end of 2012, where I was exposed to a wealth of educational materials that I intend to share back here in the Bay Area, and as Chinese immersion schools become more popular, throughout the United States.

Parent recommendations

In polling my fellow PAASSC parents for recommendations to families, specifically African Americans considering immersion, several emphasized that cultural sensitivity is a two-way street. Jones puts it bluntly: “If you can’t embrace another culture you are doomed before you start,” adding that she has actually found that there are more similarities than differences between Chinese and African American culture, including the importance of family and cultural history, reverence and respect for elders, and focus on community instead of the individual.

Lia Barrow adds that parents must seriously consider their own expectations for both the school and their children. For example, she says that no matter what race your family is “f you expect your child to attend a Mandarin immersion school because they will be the ‘only’ child with specific qualifications or to ensure that your child is ‘super’ or ‘special’, you are going to be in for an awakening. This is a booming trend and very competitive. Through this process you will find that there are numerous children that are just as focused, skilled, and bright as your child.”

I would add that both parents need to be on board, willing and able to support and encourage their child’s language development–in both the native and target languages. Language immersion cannot take place in a vacuum. Early childhood exposure is essential for success, from museum trips, music and movement to various sports, and interactions with other children. As Jones points out, “Your child has to be school-ready before even considering a program like this; eager, ready, and excited to learn.”

Helen emphasizes financial preparedness because a public school option for language immersion may not be available or practical for every family. At the same time, she recommends not stressing over the prospect of immersion itself: “It doesn’t have to be rocket science. The rest of the world teaches their kids language in their school systems.”

These first three years of our quest to raise bilingual children has taught us a lot about ourselves individually and as parents. We have learned that it is important to find ways to continue to discuss our goals and expectations of our children. We have discovered that nearly every parent – regardless of race, school type or other specific traits – shares a common, primary goal for their children: that they are able to be successful and content.

On a personal level, I have realized that my knowledge of the Chinese language and my ability to support my children’s learning are stronger than I anticipated. I am capable of helping them with their homework, providing a supportive home environment that encourages Chinese language learning, and creating a community that allows my children to feel supported an encouraged to speak Chinese outside of the classroom setting.

It has been a thrilling and often humbling journey, as my husband can attest. “If you choose to pursue a Chinese immersion education, accept that it is going to be something that you have no experience with–something that is going to be foreign to you – and you must get comfortable with not knowing,” he says. “If you have multiple children in Chinese immersion, the day will come when your children will have conversations with one another that you will have no ability to understand.”

His advice for surviving the uncertainty is simple: “Enjoy the ride.”

Jamila Nightingale is the founder of Parents of African American Students Studying Chinese. She and her family live in Berkeley, Calif. Her children attend the Chinese American International School in San Francisco.