Kindergarten is a huge moment in a child’s life. So imagine if your parents sent you to a school where they teach most of the day in a language you don’t speak, like Spanish or German or Japanese. In California, a growing number of families are choosing schools like this. It’s called dual-language immersion. Reporter Deepa Fernandes followed the Gomez family this past year as their daughter, Gemma, attended a public school that teaches in Mandarin.

Kindergarten is a huge moment in a child’s life. So imagine if your parents sent you to a school where they teach most of the day in a language you don’t speak, like Spanish or German or Japanese. In California, a growing number of families are choosing schools like this. It’s called dual-language immersion. Reporter Deepa Fernandes followed the Gomez family this past year as their daughter, Gemma, attended a public school that teaches in Mandarin.

(reposted from SCPR.org)

Despite a slightly nervous start to the school year last August, Duarte mom Brooke Gomez has one word for her daughter’s nine months of kindergarten: amazing.

Many parents experience the anxiety of their first child starting school. But for parents sending their kindergarteners into a dual-language immersion classroom, especially when the language being taught is not used at home, the questions and doubts abound. In some cases, it’s a leap of faith.

“We are an English-only speaking family,” Gomez said, the day before school started last August. “We’re not just non-Chinese, we don’t speak any other language than English in our house.”

As the number of dual immersion schools proliferate in California, many parents wonder if such programs are right for their child. How do children learn in two languages and does it help them academically?

We’ve been following the Gomez family for the past year as they posed those questions and watched their oldest daughter step into an unfamiliar linguistic and cultural world.

Gomez said the family lives near a “great” elementary school blocks from their home, but they chose to drive to Pasadena, to Field Elementary School, for its Mandarin immersion program.

The now six-year-old Gemma — elder sister to Ellen, 4, and Marlo, 2 — attended the Duarte public school’s transitional kindergarten last year and flourished. Gomez had no worries that Gemma would adjust to kindergarten, follow her teacher instructions, and keep up with beginning academics.

A bright girl, Gemma appeared ahead of the curve going into kindergarten.

Yet on the day before school began, Gomez was dogged by a feeling of uncertainty.

“It’s really scary, actually. I’m having my doubts even until today where we’re going to school tomorrow,” she told us in August. “The scariest part about it … is just sending your kid somewhere where the teacher doesn’t speak English.”

In Field Elementary’s dual-language immersion school, kindergarten students spend 90 percent of their day learning subjects in the Mandarin language. Teachers speak only Mandarin to the students, said Principal Ana Maria Apodaca. They switch teachers for the portion of the day that is taught in English, so students won’t hear a Mandarin language teacher speaking English.

“A small percentage of our kids come into the program knowing Mandarin already. We probably have about 10 percent of our kids in kindergarten this year who already speak Mandarin,” she said. The rest start their language training from scratch.

Gemma Gomez had taken a five-week summer course at the school before starting kindergarten. She learned how to address the teachers in Mandarin, count to 10 in the Chinese language, and pick up some basic letters.

For children who have never been exposed to Mandarin before, Apodaca said, it can be a little unsettling when they discover their teacher will only speak to them in Mandarin.

“The beginning of the year is tough for some of our kids,” she said. “They’re very excited to be in kindergarten and then once the instruction starts some of them are a little bit surprised.”

Apodaca said the excitement carries most kids through the first month, at which point many realize they “are very tired,” she said. “They don’t realize necessarily that they’re working so hard, but it’s evident to the adults around them that the kids are really working hard to understand what is going on throughout the day.”

Two months into the school year, as she sat in her car before the first parent conference meeting, Brooke Gomez wondered what kind of a report she would get on Gemma. She felt that Gemma was making good progress, and the then 5-year-old was loving school. But was she learning all she should given she might not be fully understanding the teacher?

After the conference, Gomez beamed and described Gemma’s progress as “pretty good.” Her teachers gave examples of Gemma’s work and some basic test results. Not only was she on track with English language work, she was picking up Mandarin at a pace beyond the curriculum’s timetable.

By the winter, Gomez was convinced she and her husband had done the right thing by placing Gemma in a Mandarin immersion program. “Gemma’s really enjoying it,” her mom said. Gemma is constantly singing in Mandarin, and her grasp of the language “is really starting to click.”

But Gomez was also having side conversations with other mothers in the program about possibly hiring a tutor after school to help the kids with their English and make sure they were on track.

It’s a common worry for parents of dual-immersion students: will their child fall behind in English and are they learning as much as peers in English-only programs? Gomez knew Gemma was being pushed intellectually each day; she could see her daughter rising to the challenge. But she thought about how her daughter might benefit from a tutor.

“I was definitely all for [a tutor] until one of the moms came back and said that she had spoken to a colleague that worked at a school that really felt like, with their age, it really wasn’t necessary,” Gomez said.

LEARNING LANGUAGE

The Mandarin language and its many dialects are the most commonly spoken language in China, and across the Chinese diaspora worldwide.

“It’s a very old language,” said Hongyin Tao, Mandarin linguist and UCLA professor. “It is linguistically distinct because of its sound system — it has four tones.” He said the “same basic sound can give you different meanings if you pronounce it with different kind of tonal patterns.”

To help her students grasp this complex sound system, Principal Apodaca has put sound mics on all her teachers. “Most of our teachers use a voice amplification system because Chinese is so dependent on the four tones of the language and having that voice amplification system helps our students hear the difference between each tone,” she said.

These differences matter a lot when speaking Mandarin, and young children are very capable of learning these as easily as they would learn a language without a complex sound system, according to Nina Hyams, another UCLA linguist.

“We are prewired to accept any linguistic input that gets thrown our way,” she said. Babies are born with a “language program,” which allows them to acquire any language. However, “with time, it’s very possible that it becomes less active and less available.”

For that reason, she is a strong proponent of teaching elementary school kids a second language.

“We know that around puberty is the point when [the language program in the brain] seems not to be as active anymore, and in this country that’s the point at which we start teaching second languages, generally, in middle school,” Hyams said. “So we’re introducing second language instruction at precisely the point where people are much less cognitively prepared to acquire a second language. It’s harder work for them, and they just don’t do it as naturally.”

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR

Gemma Gomez continued to make good progress in class. Not only was she learning math and social studies and science in Mandarin, she and her classmates were learning Chinese cultures and traditions.

The children are taught a mix of traditional and popular Chinese songs and in the older grades they learn to play musical instruments, instruction that is not common in public schools these days. The fruit of that work was displayed to parents in a shimmery Christmas-themed concert right before winter break.

In the spring, each child wrote and illustrated a book, which the school had printed with hard covers and high-quality paper. Apodaca will deliver the books to a rural Chinese school in the mountains of Shanghai this summer.

“This really provides a unique opportunity for our kids to see that their language learning has purpose not only for themselves but has purpose in a global perspective and that they can contribute to the betterment of someone else’s life,” said Apodaca.

Gemma’s book is about a little fish that learns to read. The book the fish reads “is made out of coral and the letters and words are made out of seaweed,” according to the young author herself.

While Gomez says she knew her daughter was progressing, she wasn’t able to gauge whether her daughter was speaking correctly or even if her accent was right. She quickly discovered a snappy way to check.

“I take video of her all the time,” Gomez said. “I want proof that she is actually learning how to do something. So I play it for my [Mandarin-speaking] co-worker and she tells me if it’s correct.”

Some parents have complained that students in dual-language programs end up getting drilled a lot. Field’s kindergarten teacher Tingting Mei said repetition is how she helps her students master the language.

“Most of them, they’re really good at pronunciation,” she said. Mei said it is something they work on. “If a student mispronounces the words, I will have the student repeat it again until they get it,” she said.

Gemma’s mom said she is mostly comfortable with the repetition required in her daughter’s classroom, but the issue of whether it is overdone crosses her mind. “I definitely have had that thought many times, of ‘Is this right for us?’ Because there have been days when Gemma says she learns the same thing over and over every day, and I have to think that that is normal…because they start to get very good at it.”

Gomez said Gemma now regularly talks to her younger sisters in Mandarin, and often teaches them words or phrases. In fact, the whole family has now begun using Mandarin, coached by the kindergartener.

“When we’re playing games at home, she always incorporates Chinese into everything,” Gomez said. Gemma has even taught her family how to say “hello” and “goodbye” to Chinese restaurant waiters and shop assistants.

In the final days of school, Gomez was thrilled with how her daughter’s year had gone. “She’s not reading chapter books yet, but overall I feel very comfortable with the program and she’s on track with English and math and other categories.”

Perhaps the best proof of the family’s experience this year? Both Gemma’s younger sisters will be going to Mandarin school as well.

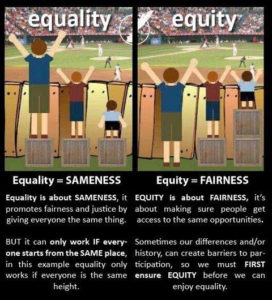

We are clear that Equity and Equality involve very different strategies and that both do not lead to better outcomes for all youth. As indicated in the picture we have to ensure equity before we can address equality.

We are clear that Equity and Equality involve very different strategies and that both do not lead to better outcomes for all youth. As indicated in the picture we have to ensure equity before we can address equality.