President Of 100,000 Strong Foundation Carola McGiffert Explains How Teachers Will Get 1 Million U.S. Students Learning Mandarin By 2020

Can 1 million American schoolchildren learn Mandarin over the next five years? Carola McGiffert, the woman charged with the task, is betting on it.

In late September, President Barack Obama unveiled the 1 Million Strong initiative, which aims to increase the number of U.S. children learning Mandarin in school from 200,000 to 1 million by 2020. The announcement follows the launch of the 100,000 Strong Initiative in 2009, which successfully increased the number of Americans studying abroad in China to 100,000 since the program began — up from just 13,000 during the 2007-2008 school year.

McGiffert, president of the 100,000 Strong Foundation, which was formed in 2013 to oversee the eponymous initiative, is also leading the new 1 Million Strong push. The goal is to get 1 million children in grades K-12 on the path to learning Mandarin so they’ll gain an understanding of both the language and Chinese culture. We sat down with McGiffert to learn more about how she plans to take on this ambitious goal.

Give us a broad overview of this new initiative.

Last fall, President Obama announced that the 100,000 Strong student goal had been reached, but obviously, there’s much more work to do. When we learned that Chinese President Xi Jinping was coming for a state visit in September, we started working with the White House to figure out the next big goal, one that is ambitious but reachable and worthy of presidential attention.

Whether you’re a journalist, or a diplomat or a business person, we want to make sure that our young people in all of these fields have the ability to work with Chinese counterparts and competitors.

Why Mandarin? What’s the point?

The view right now is that the China-U.S. relationship is in a really tough place, and will be marked by contention for the foreseeable future. That means we need to learn how to manage it, collaborate where possible, and manage that discussion so that it does not spiral in a negative direction when our interests are different. Contention and competition is one thing, conflict is another, and we can’t go down that road.

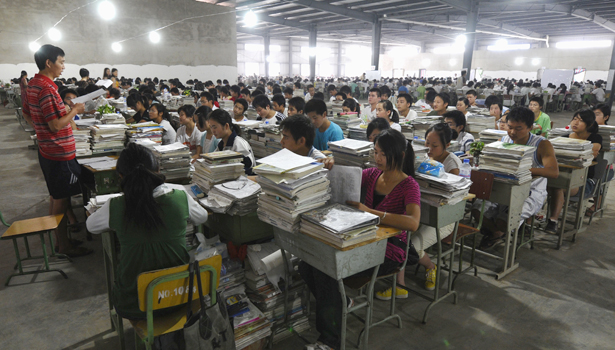

The goal is to make sure there are young people who understand the strategic importance of this relationship and can work on those issues and understand the huge role that China plays in our economy.

When I heard about this initiative, the first question that popped into my mind was: Who is going to teach these Mandarin classes?

We rely heavily on the generous support of the Chinese government, which sends us hundreds of teachers every year. While we are deeply appreciative of this and want it to continue, it’s not enough. It’s never going to scale to be able to meet the demand. We will be working with organizations like ACTFL, the American Council On The Teaching Of Foreign Languages. This is what they do — they train and support the training of foreign language teachers.

I learned that you don’t have to be fluent in a language to be an effective language teacher.

Is that a good thing?

I think it’s a good thing, because it opens the door for more young Americans who are highly proficient. It creates opportunities for them to enter the teaching field in Mandarin. Perhaps they’re not teaching the most advanced classes. I think that’s one way to get a lot of young people right out of college and graduate school to be excited about becoming a teacher and using their Mandarin skills.

How are you going to decide where these teachers are placed?

A critical component of this is our network on the state and local level. We’re going to start with a handful of partner states where we can pilot this effort, both in terms of testing and implementing curriculum as well as teacher placement. We will be coming out with those states soon, but they’re geographically diverse, led by both Republicans and Democrats, often where the Mandarin language has already been noted as a priority in the school system.

How will you make sure these classes are equitably distributed among rich and poor school districts?

From the outset of this initiative, diversity has been a top priority. It has always been about not only increasing the number, but diversity, of young Americans who study abroad in China, and it’s the same for the language component — if not even more so. Frankly, the more affluent districts, particularly in suburban areas, they already have Chinese language classes, so the need is less there. I really do think that where we are value added is in underserved and underrepresented communities.

You’re trying to get 800,000 more K-12 students in Mandarin classes. Does that sound crazy to you?

It sounds ambitious. It does not sound crazy to me. Any goal that’s worth having has to be big. We didn’t go into this sort of just picking a number out of thin air, even though 1 million sounds nice. We really did work with experts in the field in terms of K-12 Mandarin language learning, and feel very confident that if you bring all the right players and pieces together, we could make this happen.

(repost from Huffington Post)